Jewish Museum’s Christoph Kreutzmüller

(Christoph Kreutzmüller)

Dr. Christoph Kreutzmüller, a German scholar, has done seminal work, creating a database of businesses that were Jewish-owned in Nazi-era Berlin.

As I’ve said previously, Christoph’s sleuthing for his book FINAL SALE IN BERLIN, The Destruction of Jewish Commercial Activity, 1930-1945 fills a gap in the record that so frustrated me while I was seeking restitution for my family’s businesses in the German capital.

Almost incredibly, whereas the history of Jewish businesses under the Nazis was known in quite some detail for many much smaller German cities, for Berlin, for various reasons, there was a black hole in our knowledge that sucked in many a restitution seeker.

In FINAL SALE, Christoph weaves his findings into a compelling narrative about Jewish business-people’s doomed struggle in Berlin under the Nazis. The depth of detail is sensational, and Christoph’s contribution not just to the community of scholars, but also to the memory of those lost to the Holocaust is incalculable.

As Christoph is currently working on an upcoming exhibition for the Jewish Museum, Berlin, I caught up with him for this interview.

1) Please tell us something about upcoming exhibitions at the Jewish Museum, Berlin.

The Jewish Museum, Berlin opened over 15 years ago. More than 10 million people have visited. Now, we are preparing a new, permanent exhibition that is scheduled to open in 2019. My role is to curate the part of this new, permanent exhibition that shows German Jews’ reactions to Nazi persecution. This is a wonderful opportunity; I am honored and excited to have a hand in it.

(A view of the Jewish Museum Berlin)

2) What are some things or places that speak to a historical presence of Jews in Berlin that people might be surprised to see when they visit the city?

When I moved to Berlin in 1991, there were hardly any conspicuous signs of Berlin’s rich Jewish history. Guides as well as guidebooks on the topic were rare then, too. However, walking through the streets of East Berlin, I could make out the faded names of companies that previously occupied the shop spaces, which in the early 1990s were largely deserted and still marked by wartime bullets and bomb splinters. I found that fascinating. It felt like walking through a scarred, three dimensional directory to those former businesses. I wondered who the owners had been and what happened to them – but at the time, I had no way of knowing all of that.

Today, the situation is completely different.

The history of Jews in Berlin has been researched quite well. Important places and events have been marked in the cityscape. Many visitors are actually surprised by just how many different memorials there are. Some of the memorials set up by local initiatives are fascinating. I find the memorial for the former fashion businesses on Hausvogteiplatz impressive. You walk up the stairs from the subway, reading the names of the formerly Jewish-owned businesses, and then end up looking at yourself and the square – (which of course was the center of the fashion industry in the 1920’s) – in a mirror.

(A memorial plaque and mirror on Berlin’s Hausvogteiplatz)

Around the Bayerische Square, where many Jews – including Albert Einstein – used to live, there is another deeply moving memorial. All along the lampposts there are signs recalling the persecution process. In front of a bakery, for example, there is a sign telling you that the Jews were only allowed to shop in bakeries for a very limited time. And, near a former telephone booth, you are told that beginning in 1941, Jews were no longer allowed to use phones.

(A representative memorial plaque in Renata Stih’s and Frieder Schnock’s PLACES OF REMEMBRANCE project in Berlin. The sign recalls a Nazi regulation of June 26, 1941, forbidding Jews from buying or receiving soaps and shaving creams).

3) Has your database grown since the publication of FINAL SALE?

Since the publication of my book — (in German in 2013, and in English in 2015) — I have received quite a few requests for information. Often, people find a company in the online database and then ask me for additional information. Sometimes, though, people will tell me that a certain company is missing from the database, and I find that I had not previously been able to identify it as having been Jewish-owned.

That is not really surprising, as I had very strict standards regarding identification, and more then fifty-thousand entries to research. Thus, by helping people to learn more about their families’ history, my database grows – albeit slowly. In a few months I will send a new, updated version of the database to all institutions to which I’ve previously made it available: The Leo Baeck Insitute, The Wiener Library and Yad Vashem.

4) Which areas of Holocaust-related studies might you recommend for younger scholars to explore, if they are interested in going into that academic field?

There are still many paths open, and important discussions to be had about, for instance; 1) Scope of action; 2) So-called “bystanders;” and 3) How we deal with the past.

I believe that in upcoming years, there will be a strong focus on analysis of historical photographs. Pictures have long been neglected — and treated as mere illustrations – even though they are, in reality, prime sources that we need to learn to make better use of, both in historical as well as in educational contexts.

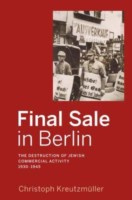

5) What do we see in the photo on the front cover of your book FINAL SALE.

The photograph was taken by an unknown press photographer on April 1, 1933.

It shows the Nazi storm troopers marching up in the morning with their posters, in order to start standing in front of businesses that they believed were run or owned by Jews. In my book, I argue that even though the Nazis called the actions a “boycott,” what happened on April 1, 1933 was actually a violent blockade – and, of course, the start of the systematic persecution process that culminated in the so-called Kristallnacht — Crystal Night (to use another typical Nazi euphemism that attempts to diminish the violence that was part and parcel of the persecution then ongoing).

I chose this picture for the cover for a few reasons. It highlights what Jewish businesses owners faced at the time. Then too, in one of the shop windows in the photo, we see a sign with the word “Ausverkauf” — (German for Final Sale, or, if you will, you could think of it as a “Going out of Business” sign). And Ausverkauf is the German title of my book. I wasn’t sure of the location of the store in this photo, but together with my daughter Josephine, I searched the Berlin directory until finally, we found the address of the branch of the men’s tailoring business “Hemdenmatz” that in 1933 was situated next to a fur shop. I thus can say with confidence that the photo was taken in Leipziger Strasse – at the time, a main shopping street in Berlin.

(The cover of Dr. Christoph Kreutzmüller’s book FINAL SALE)

To see a listing of Dr. Christoph Kreutzmüller’s German-language publications, go here.

To see FINAL SALE in English, go here.

For an English-language article about the concepts explored in FINAL SALE, please go here.

And for an English-language article Christoph wrote explaining his research, kindly go here.

Powerful reminder of the horrors of the period. Scarier still, given the current political landscape.