Dr. Marion Kaplan on Advancing Our Knowledge of the Holocaust

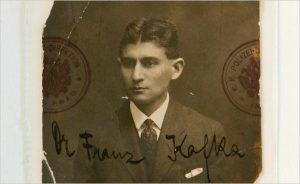

(Franz Kafka)

In two previous posts, I interviewed New York University’s Dr. Marion Kaplan about i) Women and the Holocaust; and ii) European Jewish Memoirs. For this new post in the series, Dr. Kaplan informs us about areas of Holocaust Studies that need further research and analysis.

QUESTION: For scholars interested in entering the field of Holocaust Studies today, which areas in that field do you find particularly needful of research?

ANSWER: The History of Emotions opens intimate avenues for us to explore: how did victims of the ongoing Holocaust make sense of their daily lives and how did they express this? How did they feel?

We’ve often assumed we knew, but as we take memoirs, letters, and diaries more seriously, they inform us better of frustration, hope and fear.

After many exasperating visits to inhospitable consulates, for example, one Jewish woman born in Rome — the author Carla Pekelis — concluded: “It would have taken the pen of a Kafka…to depict the world of visas in all its surrealistic absurdity; that of a Dostoyevsky to render the nightmare of the petitioners’ struggle for survival….” Finally, in front of the American consul to beg for a visa, one young man, Kurt Israel, felt himself “trembling and shaking.”

(Editor’s note: Carla Pekelis, a university professor of Italian Language and Literature, wrote an intriguing Holocaust-themed memoir, My Version of the Facts. And Kurt Israel changed his last name to Ibson after fleeing the Nazis for the U.S. Documentation of his persecution by the Nazis is important to historical research.)

Many additional areas still need investigation. Because of my interest in gender, I’d like to see more research on women’s bonding experiences and “camp-sister” relationships in extreme situations. We have seen examples of young girls adopted by young female strangers or by girls from their hometowns. Camp sisters tried to stay together, giving purpose to their lives and protecting each other as long as they could. We have also learned that women sometimes created fictive kin networks. And, it would be interesting to know the extent to which we find similar relationships among men.

I also see family histories as opportunities to highlight gendered reactions and gender roles when faced with persecution. Although family histories have sometimes blithely ignored gender, newer histories raise these issues. The history of mothering during the Holocaust also needs more attention.

One camp survivor repeated, almost as a mantra, “I had a mother,” underlining how her mother made the difference between life and death. How did mothers manage to feed, clean, or nurture children? How did they flee? For example, Lea Lazego with two children and a three-month old infant climbed the Pyrenees on foot in 1943. The important question here—besides the all-important issue of survival—is that gender roles proved malleable. Women often performed roles expected of men and sometimes vice versa.

The new concern with what has been termed “microhistories” and microgeographies during the Holocaust has opened further areas to explore: How would we comprehend relationships between fleeing Jews and those non-Jews who helped or entrapped them? Who hid or denounced them? How would we describe gender relations in a village? Or in a family bunker? Or in forests in the East? Also, we might think about sites where women transgressed gender norms—as resistance fighters — but later returned to more traditional gender norms in postwar DP camps.

**********

Marion Kaplan, Ph.D., Skirball Professor of Modern Jewish History at New York University, is a three-time National Jewish Book Awards winner.