MENDELSSOHN EXPERT MICHAH GOTTLIEB

Michah Gottlieb is Associate Professor in the Skirball Department of Hebrew and Judaic Studies at New York University.

A leading expert on the towering German-Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn (1729 – 1786), Dr. Gottlieb was kind enough to grant me this interview.

Q: How did you first become interested in Moses Mendelssohn?

A: I was first attracted to Moses Mendelssohn because of his unique position among modern Jewish intellectuals. Mendelssohn was both one of the most famous European philosophers of his day and deeply learned in traditional Jewish texts. While Maimonides had confronted the medieval problem of faith versus reason, Mendelssohn addressed the modern problem of the compatibility of Judaism with tolerance and freedom and composed the foundational work of modern Jewish philosophy, his 1783 Jerusalem, to address this problem.

While I was first drawn to Mendelssohn because of his education and achievements, I came to appreciate his humanity and ethical vision which by all accounts was reflected in his personal life. Mendelssohn had a great love for humankind and almost always privileged understanding and empathy over judgment.

After thirty years of study, I am convinced that a thinker’s actions are an indispensable barometer of his or her religious thought. An ostensibly profound religious philosophy whose author is narcissistic or cruel is worthless.

Q: Which artistic depictions of Moses Mendelssohn are your favorites and why?

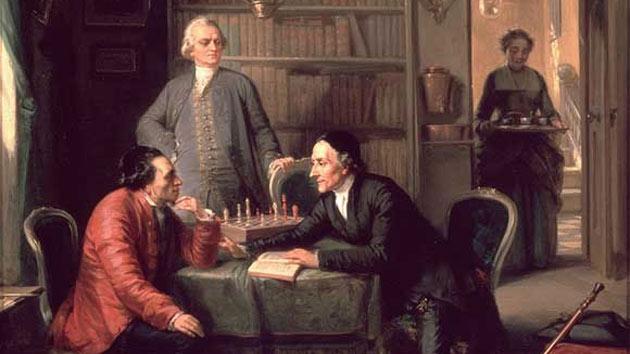

(Moritz Daniel Oppenheim: LAVATER AND LESSING VISITING MOSES MENDELSSOHN)

There is an 1856 painting by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim of Mendelssohn hosting two Christians, the Swiss pastor Johann Caspar Lavater and his best friend Gotthold Ephraim Lessing in his home. The historical background depicted is Lavater’s attempt to convert Mendelssohn to Christianity. In the image, Mendelssohn is playing chess with a black clad Lavater who leans forward and plaintively touches Mendelssohn’s forearm while pointing at a book. Mendelssohn, wearing a red jacket, strokes his chin regarding Lavater pensively. Lessing, dressed in blue, stands between the two looking at Lavater disapprovingly. Above the doorway where Mendelssohn’s wife Fromet is bringing in tea, the following words are emblazoned:

ברוך אתה בבואך וברוך אתה בצאתך (Blessed are you when you go out, Blessed are you when you come in- Deut. 28:6).

I understand Oppenheim’s painting as exploring the dynamics of interreligious debate. Lavater probably thought he was showing great care for Mendelssohn by seeking to prove to him the truth of Christianity. Lavater never saw Mendelssohn as a human subject but rather as an object to be fixed. For Lavater, religious questions were black and white, like chess games to be won by appealing to written authority. Lessing is angry with Lavater for his inhumanity and intolerance. But Mendelssohn looks Lavater in the eye and seeks to understand him. Who is Lavater? What feelings and pain and insecurity lie beneath his missionary zeal? Mendelssohn who wears red understands the power of the heart. Theological disputations are not intellectual chess games to be won, but express all too human hopes and fears. The primary religious obligation is to welcome the Other and bless him.

Q: What are some intriguing outstanding issues for research of the life and work of Moses Mendelssohn?

A: There has been a deluge of research on Mendelssohn over the past two decades with dozens of books, scores of articles, and many new translations of his works appearing. The research has been conducted primarily in the United States, Germany and Israel but has also appeared in Russian, Spanish, Japanese and many other languages. Last summer Professor Shmuel Feiner and myself were invited to deliver a series of lectures on Mendelssohn in Japan.

While much has been written on Mendelssohn, his collected writings run to over twenty-five volumes, only a tiny fraction of which have been translated. These writings include works in German and Hebrew and letters in Yiddish, many of which have received little or no attention. We still have much to learn about Mendelssohn.

It is also important to widen the context in which we understand Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn is often seen as a representative of Enlightenment Rationalism. This is not wrong, but Mendelssohn also drew on Empiricists like John Locke and had a complex relation to writers associated with Romanticism and Proto-Nationalismlike Johann Gottfried Herder, Johann Georg Hamann, and Jean Jacques Rousseau. Mendelssohn’s relationship to Rousseau is particularly fascinating and merits further investigation.

Mendelssohn’s reception also deserves much more attention. The early generation of Berlin Maskilim like David Friedländer, Lazarus ben David and Saul Ascher both appreciated and critiqued Mendelssohn, but their assessment of Mendelssohn has not been adequately explored. Doing so will not only deepen our understanding of the Berlin Haskalah but also shed new light on Mendelssohn’s thought since many of the early Berlin Maskilim learned from Mendelssohn personally.

Mendelssohn’s writings were reprinted several times and translated into numerous languages including French, English, Latin, Russian and Yiddish. His Pentateuch commentary was republished in over 30 separate editions throughout the nineteenth century. Analysis of these works will enrich our understanding of what the Haskalah meant to subsequent generations of Jews and Christians living in different times and places.

In the nineteenth century Mendelssohn was both celebrated for the triumphs of bourgeois Judaism and pilloried for its failures. Mendelssohn celebrations were held periodically especially on anniversaries of his birth and death. Martina Steer is now writing a book exploring the cultural meaning of these events. There is also a fascinating genre of children books depicting Mendelssohn as a hero to be emulated. I hope to write on article on these books soon.

Mendelssohn’s reception can provide a new way to tell the story of modern Jewish culture.

Please tell us something about your forthcoming book.

A: I have just completed a monograph on German Jewish Bible translation. In the century and a half between Mendelssohn’s translation of the Pentateuch in 1783 and Buber and Rosenzweig’s translation of the Bible which was halted shortly before the Nazis rose to power, German Jews produced 15 different translations of at least the Pentateuch more than even German Protestants produced in this period. This despite the fact that Jews were a mere 1% of the German population. In my new book titled The Jewish Reformation: Bible Translation and the Emergence of Middle Class German Judaism, I explore the cultural meaning of several of these translations which I see as engaged in a common project that I call “The Jewish Reformation.”

Luther provided a basis for German cultural identity through his sixteenth century Bible translation which helped standardize the German language. By translating the Bible into a language that the common person could understand, he also sought to reform Catholicism’s conception of Christianity by putting individual judgment at the center of religion. In this way, he helped lay the groundwork for the emergence of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. German Jewish Bible translators beginning with Mendelssohn also used Bible translation to reform German Judaism. Through Bible translation, they sought to ground visions of bourgeois middle class German Judaism in which German Jews affirmed a dual German and Hebraic cultural identity and gave priority to individual judgment in religious questions.

My book focuses on three seminal translations within this tradition each separated by about a half century: Mendelssohn’s (1780-1783); Leopold Zunz’s (1838); and Samson Raphael Hirsch’s (1867-1878). Each translator was a leading figure of a major modern German Jewish movement. Mendelssohn was the leading figure of the Berlin Haskalah, Zunz was an early Reform preacher and the founder of the Wissenschaft des Judentums (the academic study of Judaism) and Samson Raphael Hirsch was the founder of German Neo-Orthodoxy. I also discuss Buber and Rosenzweig’s Bible translation which I see as representing what I call a Jewish Counter-Reformation that rejected bourgeios German Judaism.

It is often assumed that bourgeois Judaism was primarily about ameliorating social class, economic standing, or indulging in worldly pleasure. My research has sensitized me to the centrality of ethics. For these translators, bourgeois Judaism was primarily a vision of the good life that involved cultivating a full range of human capacities including intellect, an aesthetic sense, bodily well-being and most essentially moral character.

Q: What are you next projects?

My next project will be on ethics. By ethics, I do not mean problems such as how to deal with the challenge of artificial intelligence, biomedical ethics, or environmental dilemmas. Rather, I refer to ethics in the classical Greek sense as human flourishing and happiness. Over the past several years I have been teaching a course at NYU called “Living the Good Life” that explores the ethical teachings of Aristotle, Seneca, Maimonides, Spinoza and Levinas.

I plan to write a book that conveys key ethical insights uncovered by these philosophers. I will use an experimental approach in which the reader can perform exercises to test a philosopher’s teaching about happiness and well-being for themselves.

My sense is that many of the major threats of our time most notably impending environmental disaster are the direct result of our having forgotten basic truths about human flourishing.

I have also become very interested in Samson Raphael Hirsch. There is a dearth of good scholarship on him and not a single scholarly translation into English of any of his writings. I have been working on a new annotated translation of Hirsch’s landmark 1836 Nineteen Letters on Judaism and I plan to write a new biography of Hirsch. While many scholars have seen Hirsch as a “puzzle,” I will present him as a unified thinker animated by a sweeping vision for humanity rooted in an unflinching commitment to religious liberty and ethical responsibility.

****

Michah Gottlieb’s book FAITH AND FREEDOM: MOSES MENDELSSOHN’S THEOLOGICAL-POLITICAL THOUGHT is available here.