Yale Professor Jason Stanley

My cousin Jason Stanley — who often writes for The New York Times — is the Jacob Urowsky Professor of Philosophy at Yale University.

My father Gerhard Intrator had a brother, Alexander, whose son Manfred was Jason’s father.

As Jason and I have shared family roots in Berlin, I recently asked him several questions about that city.

1) Did your father Manfred ever talk about Berlin with you?

Manfred was born in Berlin in 1932. He did not escape until he was almost 7, in July 1939. My father spoke to me often about Berlin. Strangely, his whole life he thought he lived on Ku-damm, as his stories concerned Oliverplatz, his favorite park, which he described as around the corner from his apartment. And he always claimed that the apartment in which he grew up had a large balcony overlooking the Kudamm, from which he would watch Nazi parades and beg to be allowed to join. It was only recently, a few years ago, that I realized that what he recalled as the apartment in which he grew up was the apartment of his dear grandparents, Jakob and Rosa Intrator. His entire life, he thought that was where he grew up. He loved them so much, and my sense is that Jakob and Rosa largely raised him

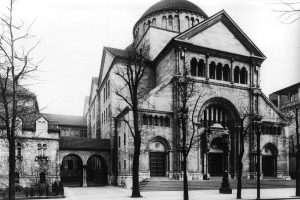

He also had strong memories of the Fasanenstrasse Synagogue, where his grandfather Magnus Davidsohn grew up. He remembered seeing it burn on Kristallnacht and being rushed from car to car. He had clear memories of the insanities of that night. He also had good memories of Berlin. He remembered the tenor Richard Tauber visiting his grandfather, and singing him to sleep. He was a fan of opera, so that was a very positive memory.

I didn’t understand my father’s childhood when I was growing up. Like many survivors, he wouldn’t speak of his own suffering, because of the feeling of great fortune he had of having escaped. But the last six months of his life, with advanced Parkinson’s and stage 4 cancer, his childhood fears came out. I have gotten a much better sense of his childhood since the Topography of Terror exhibition opened in Berlin. I have a five year old child of my own, and he always asks me what street signs say. Topographie des Terrors helped me understand the streets my father walked upon as a five year old, and the questions he must have asked his parents and grandparents. I am very grateful for that exhibition.

(The Fasanenstrasse Synagogue, prior to its destruction by the Nazis)

2) When did you first visit Berlin, and what were your impressions of the city?

My family is a Berlin family, so there was never any question about my returning to Germany, and to Berlin specifically. My first time in Berlin was in 1985, when as a 15 year old I was spending a year as an exchange student in the Congress – Bundestag scholarship program, attending Gymnasium in the Ruhrgebiet, right outside of Dortmund. I went to Berlin multiple times that year, once with a school friend, staying in a youth hostel, and once on an official visit with our exchange program. The German government had paid for us, so we went on a several day long propaganda tour of West Berlin. The Holocaust was not mentioned once. Germans were represented as victims of Stalin. Everything was about the horrific tragedy of the 119 people killed trying to cross the Berlin Wall in the previous 25 years or so. A member of the Bundestag came to speak with us about the tragedy of loss of German life caused by the wall. I agree that it is a tragedy that they were killed, but I raised my hand and asked why in three days no one had ever mentioned anything about the vastly more Jews, homosexuals, and communists who had been massacred by the Nazis, why there was absolutely nothing in Berlin to commemorate that. He blanched and his aides rushed him out of the room. I was told that I had placed the funding for the exchange program into peril.Berlin has changed completely since those days. It commemorates its tragic past like no other city on earth. As a child of a family whose existence was once erased in Berlin, I am profoundly grateful. I feel now that I can reclaim Berlin as my family home.

Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm

3) When were you most recently in Berlin, and what did you do while you were there?

I have been to Berlin dozens of times since 1985 (I also went to a year of university in Germany). I give lectures all over Europe, and with regularity I have always stopped in Berlin for a few days. Finally, after many years, I was invited by the philosophers at Humboldt University. In 2012, I was a visiting professor at Humboldt University, giving a three day long course in the Berlin School of Mind and Brain, on some of my work. Most recently, in 2014, I gave several lectures at Humboldt and the Free University of Berlin about my most recent book, HOW PROPAGANDA WORKS. On my way to give my lecture at the Humboldt Hauptgebaeude, I walked over Bebelplatz, formerly Opernplatz, where the largest book burning in history took place. Then I gave a lecture on propaganda, in German, in front of a large audience. That was very meaningful for me. I hope to forge closer ties with the philosophy department at Humboldt and bring my children there for a year one day, so they, like me, can know German and be connected to Berlin.

4) Please tell us about your ancestor Magnus Davidsohn

My great-grandfather Magnus Davidsohn was the son of Hermann Davidsohn, an orthodox Cantor. His great-uncle was Bogumil Dawison, perhaps the first great Jewish actor on the European stage. Magnus was initially an opera singer. He and his brother Max were both bass-baritones in the Prague Opera. Max went on to join the Wagner Ensemble, under Angelo Neumann, who also trained Magnus. I have a poster from the Wagner Ensemble from 1901, with Max as Siegfried in Richard Wagner’s RING. Max was also Alberich in Bayreuth in 1905, 1906 and 1908. Magnus was having a similarly illustrious career. In his multi-volume biography of the composer Gustav Mahler, Henry-Louis De La Grange discusses Magnus’s role as King Leopold in Mahler’s 1899 production of Wagner’s LOHENGRIN. But Magnus decided to leave the opera, because he no longer wanted to sing under the Christian name “Dawison.” So he became a Cantor, and in 1912, Oberkanter (head Cantor) of the grand, newly built Fasanenstrasse Synagogue, which Kaiser Wilhelm had given to the Jews of Germany. He remained as head Cantor until its destruction during Kristallnacht in 1938. He was deeply devoted to Jewish liturgical music, and to his community. He was the President of the German Cantor Union for many years. His German-language biography by Esther Slevogt was published in 2013.